Milada Pavlíková grew up in Tábor, in a family of "progressive ideas and aspirations". These were held both by Milada's father Josef Pavlík (a town physicist and chief railway doctor, but also a revivalist, chairman of the Society for the erection of the Hus Monument in Tábor and a personality of considerable cultural insight) and by the female part of Milada's family. These were mainly aunts from her mother's side – Anna Honzáková, the first Czech doctor, and Albína Honzáková, one of the leading activists of the women's movement, a graduate of the Prague Faculty of Arts of Charles University and a professor at the classical girls' gymnasium Minerva. Both aunts set an example for Milada in the fight for women's equality and inspired her to a great extent with their lives and work. Albína Honzáková even taught Milada as a class teacher at Minerva. "The girls adored our class teacher and historian," Milada wrote about her aunt. "Personally, I too am bound to her not only by family ties, but also by great gratitude as a teacher and a person whose noble character had such an impact on me in my youth." (Honzáková, 1930, p. 201)

The years at the Prague grammar school and especially the study of history also influenced the future direction of the first Czech architect: "The historical lectures were followed by trips to museums and art exhibitions of Mánes, etc., to old Prague palaces or private gardens. How I used to love going to them! The impression of such a work of art, whether it was a painting, architecture or something else, was ingrained in me and had an effect. I was beginning to learn to appreciate the beauty of the creation and really take it in with my whole soul. I think that these impressions strongly contributed to my later decision of my life path, which was then an unusual choice for a graduate of a classical gymnasium. Architecture seemed to me to be the most beautiful field, I liked it for its wide scope and the fact that all the fine arts could be combined in it into one whole." (Honzáková, 1930, p. 202)

In order to deepen her knowledge in the field, Milada also attended lectures on art at the then Union of Education and the Artistic Word - mainly by Zdeněk Wirth and Václav Vilém Štech - at the same time as she attended the Minerva Girls' Gymnasium. After graduating in 1914, she decided to take the next step on the road to architectural education. However, it was not an easy path, as studying at the "technical school" was forbidden to women at that time. She therefore studied first privately and without a degree. She wrote about her experiences: "... At the intercession of my father with progressive Czech professors at Charles University, I was accepted as a private student at the Czech Technical College. From the autumn of 1914, with the benevolence of the professors, I was able to study, even if only privately, yet to the same extent as the regular students, who accepted me collegially among them. (...) I attended lectures, sketched, worked on projects and passed my exams successfully, receiving private certificates without stamps for four years. I applied several times without success to the Ministry of Education and the Reich Council in Vienna for permission to study properly, supported by the dean's office of the faculty and the rector's office of the CTU in Prague and the main intervention of the Reich Council member Prof. Smrčka from Brno. (...) Today I marvel at my audacity and admire my optimism, but it was a kind of obsession that became the driving force behind my studies." (-ZP-, 1975, p. 10)

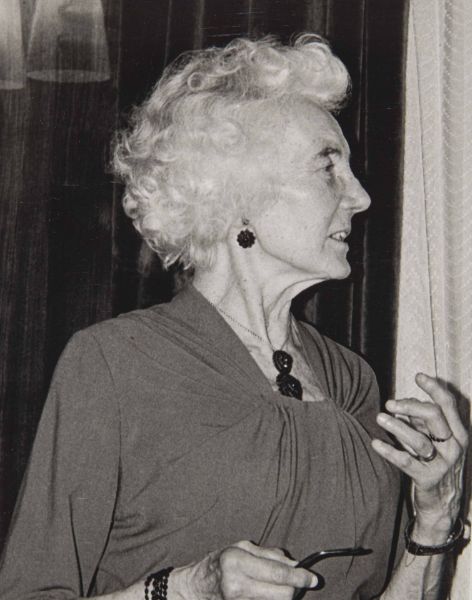

Milada Pavlíková was not allowed to study properly until the end of 1918, when her exams were officially recognised. Less than three years later, after successfully passing her state exams (with honours, on 18 June 1921), she became Czech first graduated architect. The changing times and social norms were reflected in the minutes of the commission's resolution – both the letters c. k. and the pre-printed address "Mr. Candidate" had to be crossed out on the form.

Soon after her graduation, Milada Petříková-Pavlíková (she adopted the name Petříková after her marriage to the architect Theodor Petřík, whom she married shortly after receiving her university diploma) also managed to successfully enter architectural practice. She created several projects in collaboration with her husband, who was by then an established designer and professor at the Prague Technical University, while others were developed independently.

Milada Petříková-Pavlíková's first major project was the Home for Lonely Women, intended as collective accommodation for elderly women and pensioners in Šolínov Street in Dejvice (1922–1924). A little later, the project of the Home of Charlotta Masarykova in Prague's Vinohrady district was created – providing shelter for single mothers with children (1928, together with Theodor Petřík). "The project," the architect noted in her memoir, "(...) is the same age as my third boy. At that time, this project had a special appeal for me, because the homestead was partly designed as a shelter for mothers with children. This field is particularly close to my heart, and I would like to continue more in that direction again." (Honzáková, 1930, p. 202)

The inclination towards social building projects for women and/or children accompanied Petříková-Pavlíková practically throughout her entire creative career. One can mention, for example, the interiors of the Girls' Student College Budeč in Vinohrady (1924), the club house and the bachelor's room of the Women's Club of the Czech Republic in Prague in Smečky (1929–1933, with Theodor Petřík) or later the kindergarten and nursery in Prague-Lhotka (1947-1950, with J. Mayer). Petříková-Pavlíková is also the author or co-author of several family houses.

The architect followed up her architectural designs with lectures and theoretical texts such as "The Apartment of the Independent Woman" and "Apartment Culture". She has also published several popular articles – for example on the topic of nurseries and rational kitchens. As Marie Benešová has already noted, the architect's work (both design and theoretical) was dominated by works that dealt with women's issues and related social, children's or housing issues; many of her projects were also largely collective in nature, with shared services. It can be said that by emphasizing the systematic service to otherwise somewhat neglected groups of the population, Milada Petříková-Pavlíková managed to achieve two important things. She has enriched her field – architecture – with new perspectives, approaches, ideas and concepts; and at the same time she has helped to create a better environment and conditions for the life and emancipation of women of her generation and generations to come.

After the Second World War and after the nationalisation of design institutes, Milada Petříková-Pavlíková worked in building design, where she focused mainly on urban planning. Later, she also prepared study and development plans for mining plants at the Rudny Project.

Sources:

Albína Honzáková (ed.), Československé studentky let 1890–1930 [Czechoslovak female students 1890-1930], Praha 1930, s. 201–202.

-ZP-, První česká architektka [The first Czech female architect], Československý architekt XXI, 1975, č. 23–24, s. 10.

Marie Benešová, In memoriam první české architektky [In memoriam of the first Czech female architect], Architektura ČSR XLIV, 1985, s. 461–462.

Barbora Žižková, Sociální aspekty v architektonickém díle Milady Petříkové-Pavlíkové (bakalářská práce) [Social Aspects in the Architectural Work of Milada Petříková-Pavlíková (Bachelor's Thesis)], Ústav pro dějiny umění FF UK v Praze, 2012.

Klára Brůhová, První posluchačka – arch [The First Audience – arch]. Milada Petříková-Pavlíková, ALFA – Bulletin Fakulty architektury ČVUT, 2019, č. 3, s. 5–8.

(the medallion is based on Klára Brůhová's text for the Hradec Králové Architectural Manual)