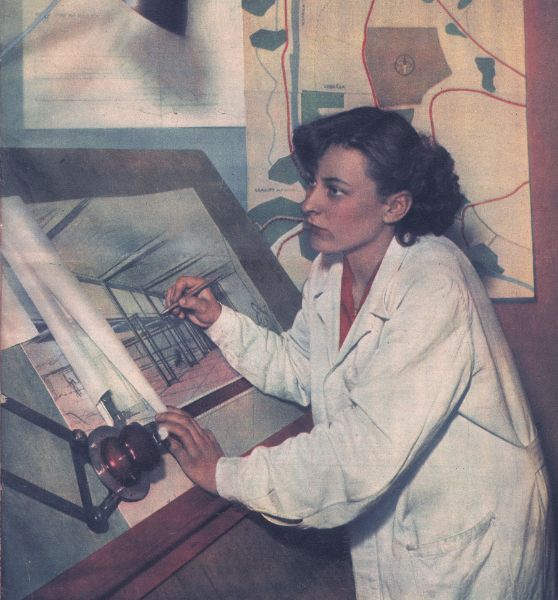

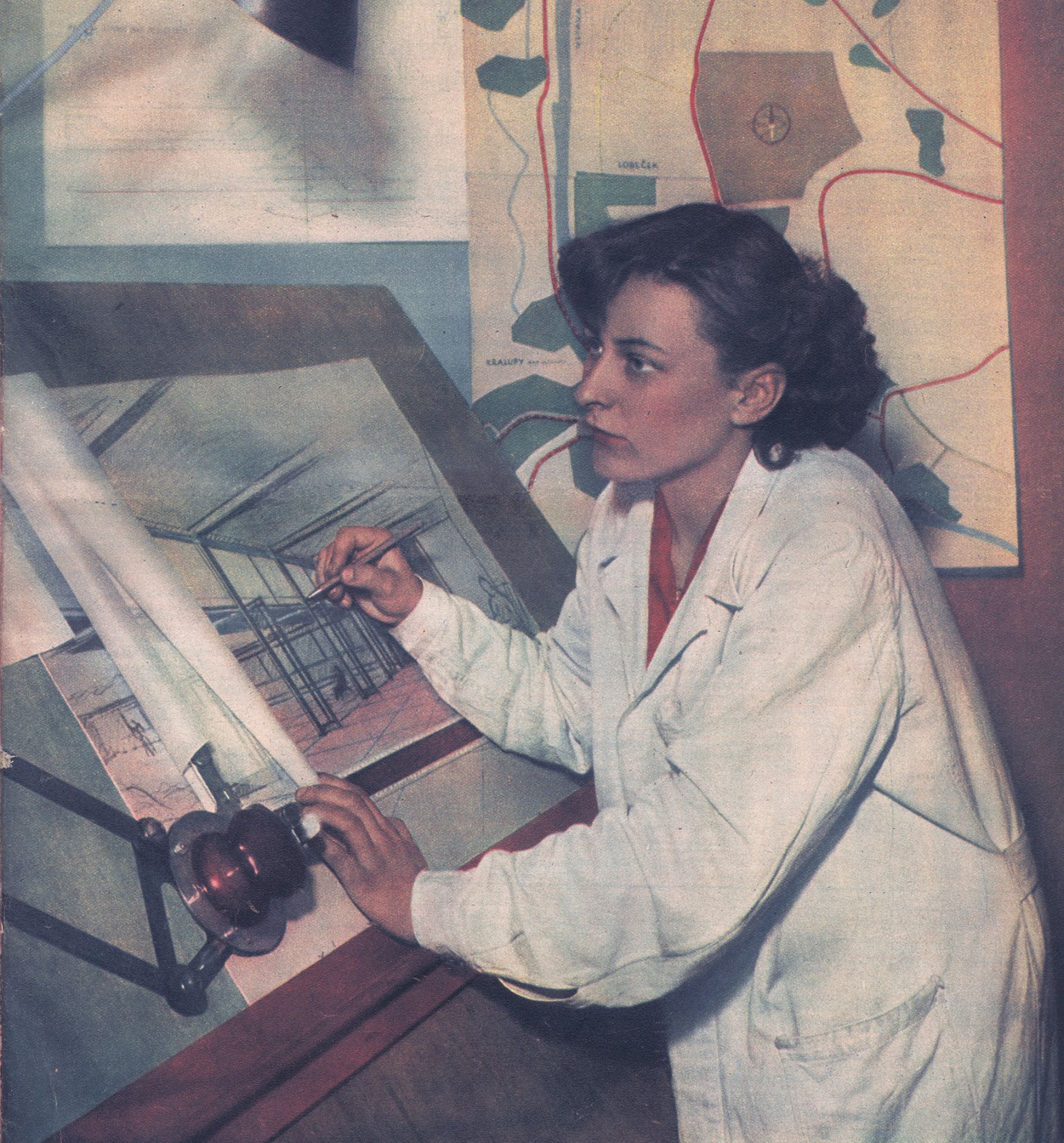

Věra Machoninová is one of the most important Czech architects of the second half of the 20th century. Her work is inextricably linked with her husband Vladimír Machonin (1920–1990), with whom she created a number of interesting buildings and designs in the Brutalist style.

During her studies at the Prague Technical University she attended Josef Kittrich's studio, after graduation she joined the newly established Stavoprojekt in Jiří Gočár's studio, which was taken over by Karel Filsak for a certain period of time. In 1958, Vladimír Machonin managed the construction of the pavilion at the EXPO in Brussels, and during the political thaw in the 1960s, the architects became more connected to international trends in their field. Together with Karel Prager, Jiří Albrecht and Jiří Kadeřábek in Pavel Bareš's studio, they won the 4th prize in the international competition for the University Campus in Dublin (1964). After winning the competition for the festival hotel and cinema in Karlovy Vary (realized as the Thermal Hotel, 1967–1977), they went on study trips abroad, focusing on cinema halls. The more liberal atmosphere in Czechoslovakia was reflected in the announcement of a number of competitions. The Machonins were very successful – they won first prize in the competition for the Kotva department store (1969) and first prize in the competition for the Czechoslovak embassy in East Berlin (1970). In the short period 1966–1971, they became independent within the Association of Project Studios (SPA) and the Alfa studio was established under the direction of Vladimir Machonin. The turning point came with the Soviet occupation in 1968. The Machonins were not admitted to the newly founded Union of Czech Architects, their Alfa studio was incorporated into the Project Institute of the Capital City of Prague (PÚ VHMP). They were prohobited to participate in architectural competitions, exhibitions and publishing. However, they were allowed to continue working on projects already in progress, such as the Kotva and DBK department stores or the Czechoslovak embassy in East Berlin.

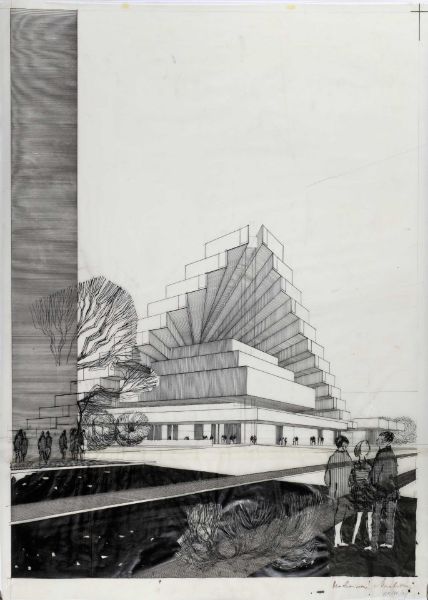

The personal style of the Machonins evolved during the 1960s. It is characterised by confident structural solutions, combining building with a generous spatial layout and distinctive morphology. In particular, Věra Machoninová emphasized her interest in the field of structural engineering during her studies – she designed the open plan of the Kotva department store (1969–1975) with its unique mushroom structure, while in the DBK Center of Home Design (1971–1981) the atrium and open plan of the main shopping center allow for a transition from one floor to another via an outdoor promenade towards the subway passage. Kotva and DBK apply atmofix, a version of corten developed in Czechoslovakia in cooperation with the Research Institute for Material Protection, to the façade. Formally, the Machonin buildings are characterised by their distinctive silhouette; the orthogonal composition of the Hotel Thermal, consisting of a low plinth and tall slender volume, is broken up by three oval cinemas that respond dynamically to the relief of the nearby river valley. A similar solution is repeated in the brutalist embassy in Berlin. The wide range of materials used, including concrete and glass, disrupts the boundary between interior and exterior.

Věra Machoninová took great pride in the execution of the building down to the last detail, creating original designs of seating and furnishings for each of the buildings. In the context of Czechoslovak architecture at the time, the use of intense colours such as red, orange, yellow and green, which together with the artworks created a unique artistic environment, is quite exceptional.

Thanks to Vladimír Machonin's managementl skills, the architects managed to negotiate quality conditions with investors and to promote non-standard solutions. Věra Machoninová searched for opportunities to implement unusual structural and material solutions with tenacity. In her own words, she rather "stayed with the project" (Vorlík 2006, pp. 188–189). In conclusion, the Machonins managed to make the most of the creative connection in the partnership arrangement, and the mutual agreement and ability to acknowledge creative and authorial merit within the creative couple. Věra Machoninová herself did not perceive any complications for women and their advancement in the field of architecture (Vorlík 2006, p. 194).

Sources:

Věra Machoninová, in: Petr Urlich – Petr Vorlík – Beryl Filsaková, et al., Šedesátá léta v architektuře očima pamětníků [The Sixties in Architecture through the Eyes of Memoirs], Praha 2006.